Latest Drug War News

These stories can't be told without your help.

Donate Today.

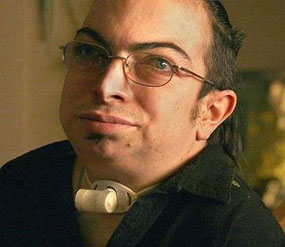

Scott Day

Medical Marijuana patient

Died Awaiting Prosecution Sept. 14, 2008 -- Great Falls Tribune (MT)

Dillon Man's Death Puts Medical Pot Back In Spotlight

By John Adams, Great Falls Tribune capitol bureau

Original article: www.greatfallstribune.com/apps/pbcs.dll/section?template=zoom&Site=G1&Date=20080914&Category=NEWS01&ArtNo=809140301&Ref=AR

HELENA -- Summer Sutton-Day said all her husband, Scott Day, wanted in life was to live with as little pain as possible while helping others find a way to cope with their suffering.

Scott was diagnosed as a child with mucopolysaccharidosis, a rare congenital disease caused by the lack of certain enzymes which, over the course of his life, spawned diverse and severe physical pain and other serious health problems.

When he was diagnosed, doctors said he probably wouldn't live to see his twenties.

He was 34 when he died Tuesday at his home in Dillon. Friends and family say medical marijuana was a key reason for Scott's surprising longevity.

They say the tragedy is he spent the final six months of his life facing criminal prosecution for growing the medicine that kept him alive. "I'll tell you what; we're all going to die. Scott was going to die sooner than most of us," said Scott's mother, Linda Day of Sheridan. "I'm not saying that this caused his death. I am going to say his death was probably a little premature, because you can't imagine what he's gone through." Day had used marijuana to treat the symptoms of his disease for the last 14 years.

"He had pain in all of his body, all over, at all times," Sutton-Day said. "There was nothing that could take away the pain, but with medical marijuana he could control it. I think that is the only reason his life was extended." In February, federal agents and local police raided Day's Dillon home, seizing 96 marijuana plants from the garden he had spent more than a decade meticulously caring for.

The Days were charged with production, possession and intent to distribute dangerous drugs, all felonies.

Neither of the Days were state-registered medical marijuana patients until after the February bust.

Sutton-Day said Scott's health dropped off precipitously following the raid because he could no longer find adequate supplies of high-quality marijuana, and his constant fear of jail time lead to bouts of depression and anxiety that exacerbated his illness.

"He was stressing out so bad about his health because there was nothing that we could do to replace what they had taken away," Sutton-Day said. Those close to Day say he is a prime example of the patient voters had in mind when they overwhelmingly passed a ballot initiative in 2004 legalizing the use of medical marijuana. Supporters of medical marijuana say Day's case demonstrates the serious gaps in the law and in law enforcement officials' appreciation for the legitimate medical use of marijuana.

Fear of Prosecution

When voters passed the Medical Marijuana Act in 2004 by the largest margin in the country, Montana became the 11th state in the nation to legalize its medicinal use.

Tom Daubert is the founder and director of Patients and Families United, a support group for patients who use medical marijuana and other patients who suffer from pain, whether they use medical marijuana or not. He said many sufferers of chronic pain and serious illnesses were overjoyed when they were finally able to find legal relief in a drug many had used illicitly for years.

But marijuana use is still outlawed by the federal government, leaving Montana's medical marijuana patients in limbo between state and federal authorities.

Besides the legal gray area, Daubert said, Montana's law limits patients to possession of six plants, or one ounce, and that's not adequate for patients like Day.

"Scott would never have been able to meet his needs for a steady supply for medicine under our six-plants, one-ounce limit," Daubert said. "Like many patients, he had multiple conditions and systems, each one of which responded to a different strain of marijuana. Day's mother said anyone who knew Scott knew he wasn't a drug abuser or dealer. She said all her son wanted was to cope with his symptoms so that he could go on living. "No one who ever knew him would believe he sold pot," Linda Day said. "For one thing, they are as poor as church mice."

Sutton-Day said both she and Scott had the necessary doctor's recommendation to use medical marijuana, but they declined to apply for state "registry identification card" for fear of being put on a list. She said Scott was a genius when it came to growing different strains of marijuana to treat different symptoms of his disease, and his doctor advised him to "keep doing what they are doing" without registering. "He was fearful of the government and fearful of prosecution," Sutton-Day said of Scott's longtime physician. "He told us specifically that a sheriff would come to our house. He was fearful for Scott's safety. He didn't want to put us on a list."

Contrary to popular belief, law enforcement officials are not barred from finding out who is on the state medical marijuana registry, said Roy Kemp, deputy administrator of the Department of Health and Human Services' Quality Assurance Division.

Kemp and one other person at QAD are the only two people in the state with access to the state patient and caregiver registry, but they will verify a patient's registration status if asked by law enforcement. "They have to give me a name, and I'll verify the name," Kemp said. "I will verify 'yes' or 'no' on the name."

That's why some patients are fearful of registering, said Eric Billings of Lewistown.

Billings, a longtime sufferer of HIV/AIDS and board member for Patients and Families United, has been using medical marijuana since 1996. He said medical marijuana allows him to use fewer and fewer painkillers and other drugs to manage the side effects of the anti-viral cocktail he takes to fend off AIDS. He's also a caregiver for five other medical marijuana patients, which means he grows and supplies marijuana to patients who can't grow it themselves. He said that in the last six months, he's endured numerous visits from police and had a significant number of his plants confiscated in what he believes were unlawful raids.

"I've been investigated by police. I have had them come to my house and threaten me that if I didn't let them search my house the county attorney would get a warrant because he knew I was a registered patient," Billings said. Nearly a year ago, Missoula medical marijuana patient Robin Prosser committed suicide less than a year after drug enforcement officers confiscated a shipment of her medical marijuana in-transit from her state-approved caregiver. Prosser, perhaps Montana's most outspoken advocate for medical marijuana use, said caregivers around the state were fearful of providing her medicine after that.

"She killed herself because she couldn't endure the agony and the pain and the sense of hopelessness," Daubert said. "Our love for Robin Prosser and Scott Day are going to drive us to continue fighting for patient's rights and to improve the law to make it more workable for suffering patients."

Needed Reform

Beaverhead County prosecutor Jed Fitch said Summer and Scott Day's case has caused him "serious heartburn."

He said he agrees that if anyone in the state deserves protection under Montana's medical marijuana law, it's patients like Scott Day. But the Days never applied to the state marijuana registry, Fitch said, and they had far more plants than allowed by the law. "I liken it to an elk tag," Fitch said. "If you decide you want to go elk hunting, you have to get a license and a tag before you go out there and shoot an elk. If you don't you're in violation of the law. If you shoot more than one elk you're in violation of the law. The analogy is you should get the (medical marijuana registry) card before you have marijuana in your possession." Fitch, who inherited the Days' case in May when he was appointed to take over for former county attorney Marvin McCann, said he never met or saw Scott Day until a hearing in August.

"I knew he had severe medical conditions, but I didn't see him," Fitch said. "You can hear that, but until you see him ... there's no doubt when you see him he's got severe problems. That increased the heartburn level." Fitch said he wrestled with the facts in the case, but the fact remained that the Days broke the law.

"In my opinion, he wasn't covered by the protections in the law because he wasn't a registered user," Fitch said. "It's my opinion that if someone had a registry card, I don't think the arrests would have been made." Fitch said he is not sure if he would have handled the case any differently if he was in McCann's position at the time of the original raid on the Days' home, but he said he agrees that the law needs to be reformed in order to prevent the prosecution of citizens like Day.

"What I'm concerned about is that on one side you have people who want full decriminalization of marijuana," Fitch said. "They are allowed to have that position, but when people see a 350-plant operation in Livingston, I don't think that's what Montana citizens had in mind when they passed the medical marijuana act. I'm afraid that Montana citizens are going to say, 'This isn't what we had in mind,' and they're going to throw the whole thing out." Fitch said he hasn't decided if he will continue to prosecute Summer Sutton-Day.

Linda Day said it's frustrating for patients and their families who are caught up in the political and legal battle over marijuana when all they want is to be left alone to treat their pain and suffering.

"We aren't the kind of people who abuse anything. We don't believe in abuse of alcohol or prescription drugs or marijuana or medical marijuana," Linda Day said. "But this is so different. What's so sad to me is that it can help so many people if it's used correctly."

Scott's mom said the state needs to do more work on the medical marijuana law so that patients like her son can get the treatment they need without facing fear of prosecution and jail time.

"The policy that they have now is inadequate," she said. "They need to find a way that they can make this available to people who truly need it. And they need to set up something so this doesn't happen to people." In the end, Scott's mom hopes something good eventually comes from his death.

"He would have been proud to be a poster child for this movement, because he did know how much it helped people," she said.

Posted 9/24/08